“Low-Conflict Contracts in Underground Construction” – An Appeal for More Cooperation and Less Confrontation

In May, 2020, the German Tunnelling Committee (DAUB)1) published its recommendation on „Konfliktarmer Bauvertrag im Untertagebau“ (Low-conflict contracts in underground construction) [1]. A concise outline of the content of this recommendation has been presented in the 03/2020 issue of tunnel [2]. Four members of the final editorial team of the DAUB workgroup wish here to provide a deeper insight into the motivation of the DAUB in publishing this recommendation.

1 Introduction and General Information

Contracts for underground engineering projects are very complex documents. In such an agreement, an engineering work, which is to come into existence in many cases only many years later, is to be described in the form of words and drawings. And not only as the end product (the engineering work), but also the path to it (construction management, dates and deadlines, site accessibility, etc.) as well as the boundary conditions (location, preceding works, parallel works, follow-up works, construction law, etc.). Developments accomplished in recent years permit three-, four- or even five-dimensional specifications via BIM.

In Germany, public clients are required to put the construction services they need to tender in accordance with VOB/A (German Construction Contract Procedures), this being an essential requirement. VOB/A defines in Article 7 Schedule of Works (1) 1: “The service is to be described clearly and in such exhaustive detail that all companies have the same understanding of such description and are able to calculate their prices with certainty and without any extensive preliminary work” [3].

The frequent conflicts between the contracting parties in the current implementation of construction contracts show that this requirement is not so easy to implement. It is necessary to bear in mind that, from its historical conception, VOB is more orientated as a standard for craftsmen‘s services and smaller civil-engineering contractors, and not for major infrastructural engineering projects.

1 | Low-conflict contracts should also be prepared for new extreme situations such as civil protests during construction –

1 | Low-conflict contracts should also be prepared for new extreme situations such as civil protests during construction –

example: Stuttgart 21 (the picture shows the demolition of the northern section of the main station)

Credit/Quelle: DB

The majority of large infrastructural projects involve engineering works of very large dimensions. The financial volume of construction is rarely seven-digit, and instead usually eight, and frequently even nine-digit. The “time” dimension always involves a number of years, and occasionally even exceeds a decade. In view of such a large time period, requirements can be changed frequently during the course of the project, whether they apply to changes to codes and standards, modified requirements made by the client, or by the social environment (Fig. 1), etc. The knowledge gained in commissioning of similar projects also have effects on project developments on such long-term projects, these frequently involving the application of higher safety requirements in the tunnel.

Tunnels practically always necessitate a more or less complex operational and equipping technology and there are, as a result, highly specialised follow-up works, which depend immediately on the tunnel construction itself (fixing, openings, cross-section dimensions, etc.). Thus, pronounced interactions between the tunnel construction and the operational and equipping technology arise. The equipping-technological planning is seldom to never available in the necessary depth of detail at the time of award of contract for the tunnel construction.

In the case of tunnels, it is necessary to take into account that the subsoil has a significance totally different to that of other engineering structures. It is, in fact, the most important construction material for the creation of the future cavity – but with an extremely great potential bandwidth of characteristics. Tunnel-engineering assessments, which include general findings concerning the geological formations and additional “pinprick” data (core drillings with a standard diameter of 100 mm), are used to determine characteristics data in order to describe and define the ground concerned within a large region. With the help of this data the assessor documents

and forecasts the anticipated ground behaviour within a plausible bandwidth. The ground analysis becomes a component of the agreement, which describes the

anticipated geology in terms of facts and figures and also includes an interpretation of the ground behaviour by the assessor, in particular in terms of the interaction between the ground, the engineering structure and the construction process. Homogeneous sectors are defined to permit the summary of comparable geological properties.

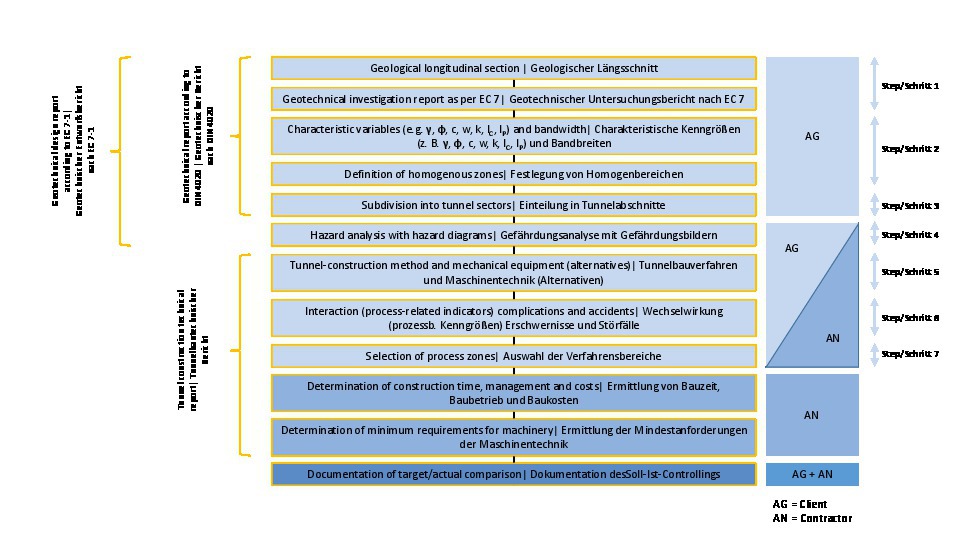

During the course of construction, the geology actually assumed will very frequently result in modifications to the strata sequences described in the ground analysis and in the geomechanical characteristics. This then also necessitates modification of the predicted model of the ground. The homogeneous sectors then also experience deviations of greater or lesser significance. The milestones for processing of the ground analysis are shown in Figure 2.

2 | The flow sheet for the subsoil shows the necessary working procedures in the field of subsoil exploration, from the project concept through to project completion. It illustrates that the complex of “subsoil” is not completed with a single subsoil analysis at the time of the draft planning but must, instead, be maintained and supported throughout the entire project period

2 | The flow sheet for the subsoil shows the necessary working procedures in the field of subsoil exploration, from the project concept through to project completion. It illustrates that the complex of “subsoil” is not completed with a single subsoil analysis at the time of the draft planning but must, instead, be maintained and supported throughout the entire project period

Credit/Quelle: DAUB [1]; translation/Übers.:Bauverlag

These individual aspects illustrate that the well-meant requirement of Article 7 (1) 1. cannot be fulfilled for a tunnel project in the sense of VOB.

Such mutable boundary conditions can result in a very wide spectrum of differing points of view in the contracting parties. These fan out between the (extreme) positions of “is taken into account in the existing contract prices without ifs and buts” and “results completely in the negation of the contractual basis”.

It is rational, in order to avoid such conflicts wherever possible, to incorporate in such contracts more extensive modular elements which contribute to a “low-conflict” implementation of the agreement. Ultimately, it is, always, the contracting parties and, in particular, the decision-makers who have to reconcile with one another. It is, however, significantly easier for the decision-makers to agree on a contract addendum or a supplementary agreement if such general rules and procedural instructions are at least provided in the form of “bridges” for many aspects in the agreement.

2 Explanatory Notes to the DAUB

Recommendation

We examine here below the three thematic sectors of the DAUB recommendation [1]:

Section 3 Recommendations for technical planning (“Practicable Design”)

Section 4 Design of the performance agreement items (“PA items”)

Section 9 Rules of cooperation

The project author is able to achieve significant advances and improvements for his project by applying these three sections in particular when drafting the contract. The complete application and internalisation of the DAUB recommendation will nonetheless lead to even better results.

2.1 Practicable Design

This subject has been one of the central items of discussion by the workgroup in all years. As a result, the DAUB has coined the new term, „Practicable Design” in its discussion paper [5]. According to the definition on page 49 of the paper, the „Practicable Design” is based on a “design ready for implementation, which can be executed within a self-contained solution concept in a realistic construction period with only low risk and cost-effectively”. The term „Practicable Design” cannot be found in the HOAI (Official Scale of Fees for Services by Architects and Engineers) neither in Article 43, Performance Profile Engineering Structures nor in Article 48, Performance Profile Traffic Structure. The same applies to Article 51 Structural Design, which also does not include this term.

The necessity of defining the new term „Practicable Design” derives, inter alia, from the following analyses, which are based on observation of the current situation:

Very few projects in Germany are planned by chronologically working through the Performance Phase 1 to 6 before a contract is made in Phase 7. This is, in fact, not at all possible in tunnel engineering, because the precise parameters for the construction planning of the „engineering structure“ and for „support planning“ are, at any point in the tunnel, either unknown or known only as an imprecise forecast derived from the subsoil model. The requirements for a subsoil model are also defined in the paper [5].

In tunnel engineering in particular, there are many technological subjects that are introduced only by the bidding or, in the case of award of contract, the constructing company. Strict prescription of a fixed and completed construction planning would be an inhibition of innovation on the construction sector.

Also not to be neglected are, unfortunately, formal aspects whereby the Performance Phase 5 (construction planning) is assigned by some clients to construction costs, whereby the funds for construction planning can only be provided at the start of construction. In this way, circumstances that basically necessitate profound investigation at an early stage are postponed to the construction planning phase to be carried out by the contractor after the contract has been awarded.

Aspects of Construction Management in

the Practicable Design

The DAUB understands by the „Practicable Design” a planning procedure which describes and clarifies all main aspects of the engineering structure and the construction

management in such a way that rational boundary conditions are assured for all participants in the competition. Especially the client‘s responsibility for thorough consideration of the construction management prior to the conclusion of the contract is a departure from previously frequently used methods (see [5] for more details). The funds for at least the planning services going beyond Performance Phase 3 and 4, which are described below, should be provided in the scope of the project preparation prior to the award of contract.

All approvals for the items following are part of the subject matter of construction management:

Site noise

Site accessibility and servicing

Adequacy of space for land utilisation incl. sampling

Site office and working accommodation

Where necessary, in tunnels using segmental support: Analysis of the transport logistics or an on-site production facility as an alternative

A further important aspect of construction management is the determination of a realistic construction period, complete with pre- and post-construction period. The pre-construction period includes more than the twelve working days provided in Article 5 (2) VOB /B [4], but also times for the formal formation of a consortium, preliminary planning discussions, detailed planning of the site setup, initial construction planning and its approval. Technical planning including hazard assessment should be advanced to such an extent that it includes the results of management phase 3 and 4 as minimum standard. The existing building law should be evaluated by the client and incorporated into the tender documents.

More Detailed Aspects of Draft Planning

in the “Practicable Design”

In addition to the construction management aspects, a more detailed fundamental consideration on the topic of the “Practicable Design” should also be the definitive parameters of planning intensity. In an extremely complex topography or geology, the spacing of the relevant transverse sections may need to be significantly compressed. This is necessary in order that the bidders are able to get an understanding of the spatial circumstances in the same way. Especially for mechanised tunnelling the “Practicable Design” also includes a failure analysis with possible sectors for preventative servicing/maintenance in the case, for example, of lowering of support slurry or of ballasting operations on the surface. Possible technically equivalent solutions at the boundary between EPB and hydro shield must be evaluated in good time in the “Practicable Design”.

2.2 Shaping of the PA Items

These remarks concerning the DAUB workgroup on low-conflict contracts relate to a unit-price contract. In tunnel engineering, in particular, there are extremely different concepts and points of opinion concerning unit-price contracts in the fields of excavation and support. In practice, the separation of the purely tunnelling activity into „excavation and support equipment“ as a cost item and a „time-related costs“ [6] as a second cost item has proven very worthwhile.

In addition, the tunnel-dependant on-site overheads are to be factored in using the customary items such as ventilation, belt conveyors, materials management, vehicles, workshop, tunnel-engineering management, etc. Also to be added are the non-tunnel-related on-site overheads which include, among other things, the site office, project management, quality assurance, planning, claim management, etc.

It is essential, for a low-conflict contract, to implement a tidy separation of services in the contract. It is also important to clearly define the boundary conditions for equipping, provision, site clearance and re-equipping for a different construction phase.

Also important is the definition of the principles of provision times clearly, in order that unequivocal rules of remuneration exist. The rules should also take account of the entrepreneurial risk so that the contractor can achieve better remuneration per time unit if his planned performance is exceeded.

It is also important that alternative and/or contingency items in the service specifications can be used to build up a modular remuneration system for changed circumstances. In this way, many topics that were previously worthy of supplementation can be converted into pure accounting supplements. This is intended to increase the contracting parties‘ ability to act and the decision-making processes can be carried out by the construction site team.

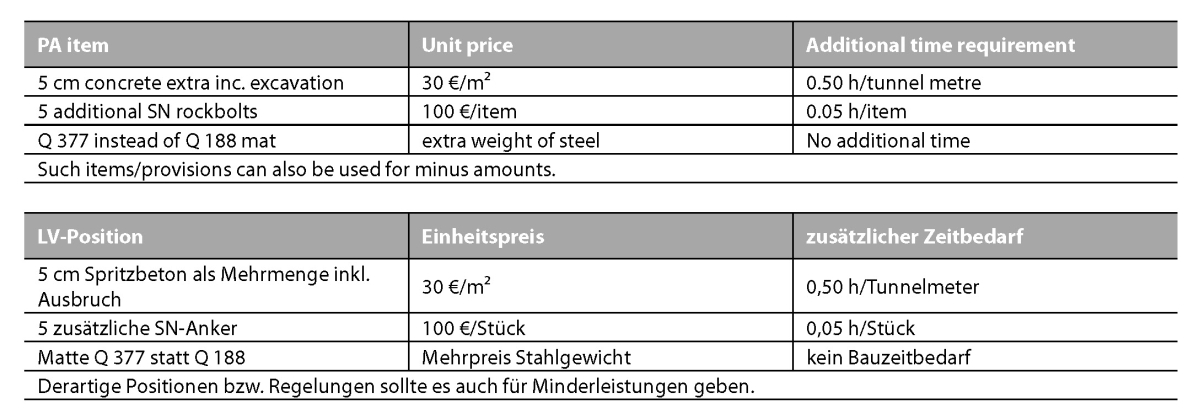

An Example:

In the course of the excavation it becomes apparent by the geology that 5 cm of shotcrete more, four rather than three rockbolts per 10 m² of wall surface area (i.e. five rockbolts per round) and a Q 377 mat instead of a Q 188 are required. A low-conflict agreement will then contain not only the unit prices for such extra quantities, but will also include time rates, which specify the extended period for the provision costs in the target plan (Table 1). The details of “unit price” and “additional time requirement” are subject to the rules of the competition and are offered in corresponding alternative and/or contingency positions.

Table 1 | If alternative and/or contingency items in the service specifications are used to build up a modular remuneration system for changed

Table 1 | If alternative and/or contingency items in the service specifications are used to build up a modular remuneration system for changed

circumstances, many topics that were previously worthy of supplementation can be converted into pure accounting supplements

The contractually ruling element in a low-conflict agreement is, in this case, the determination of excavation classes/tunnelling method selected, which must be agreed between the contractor, the client, the senior site management and the site supervision.

2.3 Rules of Cooperation

Customary contracts attempt to describe to the best of the knowledge of the parties the construction “product” and the boundary conditions. Additionally, the agreement and the general, special and supplementary contractual conditions generally only specify the provisions in case of disputes.

The DAUB recommendation [1] contains the clear note that the clients and the contractors should not only promote equitable contractual models but also consistently realise such recognition also in the competition and in subsequent implementation of the contract, from award of contract right through to acceptance of the finished work.

This includes a comprehensive bill of quantities, which both contracting parties must support in the sense of a joint project objective. Any omissions or contradictions detected by a contractor shall be eliminated in the course of the assessment of the bids. The frankness and transparency of both partners is necessary for this purpose.

The tasks, responsibilities and decision-making competencies must be decided for the construction phase in such a way that as many decisions as possible can be made on the spot by the site organisation. It is then important that employees who have received the necessary responsibilities by their superiors are sitting on the table, able to make the final decisions. Technical solutions are thus emphasised in the decisions made and conflicts in contract implementation via potential tactical and strategic considerations are avoided. Where conflict situations nonetheless occur, clear escalation routes should be provided in the contracts, including dispute-mediation models.

Correspondence should be simplified. Joint discussions using modern digital aids (such as BIM, share-point or common digital project files, for example) are more expedient than interminable mail traffic.

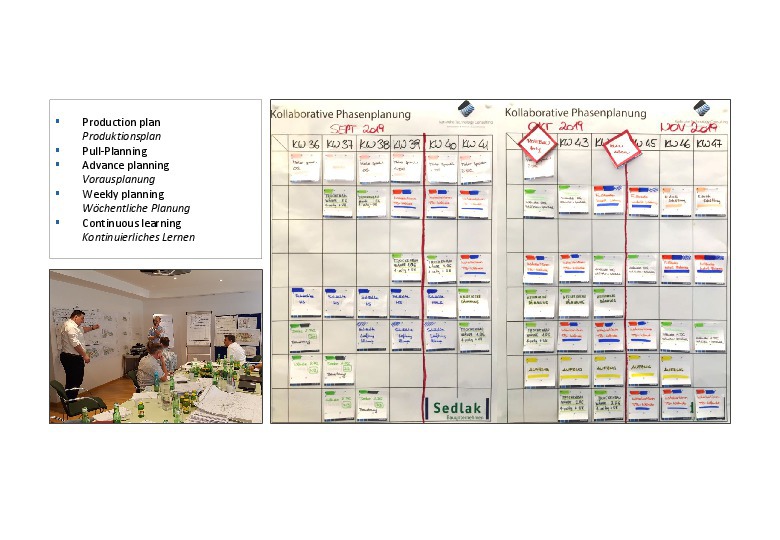

It is also recommendable, in order to attain the ever again required boosting of productivity in civil engineering, to apply the methods of “lean management”. In this context, an essential element for effective cooperation is the “last planner” methodology (Figure 3).

3 | The Last Planner method by Glenn Ballard und Greg Howell is an effective control element for planning and implementation processes. The process operations are discussed regularly with all the participants necessary for the end product. Here, all relevant aspects of the entire project must be appropriately taken into account, right through to construction acceptance and commissioning. Normally, a six-week preview is discussed each week, with an assessment of the degree of fulfilment

3 | The Last Planner method by Glenn Ballard und Greg Howell is an effective control element for planning and implementation processes. The process operations are discussed regularly with all the participants necessary for the end product. Here, all relevant aspects of the entire project must be appropriately taken into account, right through to construction acceptance and commissioning. Normally, a six-week preview is discussed each week, with an assessment of the degree of fulfilment

Credit/Quelle: Karlsruhe Technlogy Consulting

The DAUB recommendation [1] provides the following advice for cooperation for the process of execution planning:

“For all, and for critical planning packages, in particular, the use of planning and approval conferences is recommendable, in order to attain common solutions and to also take decisions promptly. Such conferences should emphasise the solution of the technical issue and its documentation; the contractual and commercial aspects should, wherever possible, be reserved for other bodies.”

The planning body is thus provided with the competence for deciding deviations in the contract target by mutual agreement. The project thus has the opportunity of passing through the planning processes in a very lean state. In addition to the significantly upgraded planning discussions, the approval conferences will make a decisive contribution to an unhindered and thus less conflict-encumbered project implementation.

We then arrive at a very important feature of contract implementation, the subject of contract augmentations – also known as „claim management“

3 Claim Management

As mentioned above, the objectives of the VOB/A are wishful thinking especially for a contract in underground construction. In the field of contract awards, there are to this day no ideal, generally applicable award criteria.

Although purely monetary aspects are no longer solely relevant, they still have a very high priority. The anticipated quality of the contract implementation is, however, no award of contract criterion. As there are still no provisions in the contracts as described in Chapter 2, current contractual practice shows different patterns of behaviour depending on the quality of the contract and the cooperation between client and contractor. Based on the actual observations in execution of construction and the external influencing factors, a more or less pronounced „claim“ and „anti-claim“ behaviour prevails. This fluctuates in a bandwidth between the possible variants „constructive-effective“, „destructive“ and „claiming as an end in itself“.

The decision in which of the three stages (and the corresponding intermediate stages) a construction contract in underground construction is executed depends on the parties involved, the respective decision-makers and the economic necessities of the contracting parties.

In many projects, today‘s claim management leads to the greatest potential for conflict and to a lack of understanding for the approach of the contractual partner. The aim of low-conflict contracts in underground engineering is that of reducing or even eliminating the potential for conflict and for advocating fair and equitable cooperation. Modules and potentials are described in the recommendation of the DAUB [1] in Items 2 to 11 and dealt with for certain individual aspects in this article in more depth. In all cases, the persons acting retain the responsibility for decision.

4 Social Aspects – Conflict vs. Cooperation

Why is a totally different way of observing the low-conflict agreement necessary in underground engineering? This is illustrated by the actual implementation of numerous present-day agreements.

How does a typical conflict arise?

The most important aspect in this interaction is humans. Agreements are implemented by people. It is not possible to say that Company A is very fond of making supplementary claims, Client B is extremely formal and is not fond of making decisions. These statements only apply to departments or to individual people.

Large tunnel-engineering projects are generally handled by three principal parties during the realistion phase: the client, the construction contractor and the site supervision team deployed by the client. Additionally, there are the assessor and the experts responsible for the examination and approval of planning.

In the majority of models practised nowadays, the employees of the various contractual parties work in their own premises, away from the construction site and spatially widely distributed but working on the same topics – but from a number of different viewpoints. Let us examine a few typical examples of non-holistic points of view:

The construction manager wishes to build effectively, to conserve resources and to progress quickly

The construction planner, often a subcontractor, wants to produce plans from his own office at relatively low effort and without in-depth knowledge of the location

The construction supervisor searches for discrepancies between planning and construction target

The plan reviewer and the expert prefer to ask a few more questions for further clarification or assurance

The client will not decide until all process signatures have been obtained

The construction manager is requested to revise the planning and augment more detailed documentation

The construction planner is annoyed, because in his opinion he has delivered very good planning after all; he submits an internal supplement to the site manager and takes time to draw up a revised plan without dealing comprehensively with all questions from the inspecting organisations

The plan reviewer and the expert are annoyed about the failure to take account of parts of their inspection notes and, from their point of view, ask the same questions again, usually with comments on their annoyance and further, more detailed questions

and so on …

After a few such escalation stages, the construction manager will quickly ascertain that he is not getting anything built and asks himself how he can nonetheless additionally cover the ongoing costs. He places a claim or an extra-cost demand. The vicious circle has started.

This may be a bit exaggerated - but if you think honestly about one or the other of the construction sites you are in charge of, you will know to a greater or lesser extent about these behaviours of the different parties involved.

The conflict has arisen at the latest by the claim or the extra-cost demand. The escalation illustrated using the example of a planning process arouses various behaviour patterns in the persons involved:

“I’ll show them that I’m right”

“Now I’m going to be totally formal and use every single passage of the contract”

“Let’s get over it and solve the problem”

“I prefer to tackle the other project on my desk, since there my efforts are appreciated”

What does that mean for those involved?

How many of these behaviour patterns are actually exhibited by individuals in this example of a planning process varies – but since people generally tend to strive for harmony, frustration eventually sets in. Frustration results in loss of motivation, lost motivation results in diminished quality. The poor quality noticed is then recorded in the form of a deviation report or a defect notice. The defect notice leads to further justifications, frequently with differing points of view, and ultimately a new and broader conflict arises.

This vicious project circle is especially critical in the present time. In the field of transport infrastructure and in underground engineering, there are significantly more tasks than there are people who are prepared to tackle these very exciting technical challenges. And in tunnel engineering there is, in addition, frequently the extra challenge of tackling these tasks well away from all social centres. Infrastructure projects frequently pass through less populated regions in order to link the centres. And this working environment, in site containers and tiny places with no cultural life can often be not especially attractive for younger people.

How to focus back on to the engineering task?

Due to their demanding objectives, tunnel engineering projects require a high level of personal commitment. If the working situation is also poor, as a result of the frequent conflict situation described above, the result will be employee fluctuation. Frequent changes as a result of employee fluctuation exacerbate the working situation even more, due to the problems of loss of knowledge, the need for familiarisation and, temporarily, unfilled vacancies.

The situation described also results in a large volume of waste of working effort. Employees of all participants make great efforts on the same tasks, but with a different point of view. They are excessively tied down by the justification discussion until the question of “Who is right?” has been answered. But this working time is then lost for the product. In the field of plan approval or processing of claims, the three participants can easily assume a percentage of between 25 and 33 % at which all parties work simultaneously but in a different orientation or a divergent objective. This is essentially due to the fact that plans are drafted by planners and passed into a plan-management system without accompanying explanatory agreement. The examiners review the plans without query, even if they have understood the thoughts of the planner only partially. They then produce an examination report from their viewpoint, of the circumstances, of which the planner, for his part, does not understand everything and cannot make any reliable correction. The communication process is lost.

How can we improve the planning process?

For this reason, the target in a low-conflict agreement for underground engineering projects is that of finding solutions in the planning process that will break down the walls between the participating persons and transform the underground structure into a joint project. The entire route to the inspection document should, however, be designed in such a way that all participants can contribute their knowledge and, as far as possible, work within an “open or common space”. Best of all is if this “open or common space” is, in fact, a joint office or at least an office building. Personal interchange and understanding of the viewpoint of the other person are just as important as the combination of all experience from the team members working on the “tunnel” product.

Assessment of the contract target should never be left out of account; but if all those participating agree that a procedure differing from the contractually agreed one is technically more rational, this procedure should be adopted for implementation. The necessary changes to the contractual provisions should be implemented as quickly as possible on the basis of the contractual elements.

Technical decisions within the planning process are usually so cost-intensive because an enormous delay arises regarding construction approval and actual construction. Discussion of who bears responsibility for the change, which has now consumed much time, further delays construction implementation and is significantly more cost-intensive than actual modification of the planning itself.

Joint drafting of solutions for the “tunnel” product as engineering tasks – without great dispute and conflicts – will arouse much greater enthusiasm in young engineers for tackling the tasks with commitment. Because then there will be partial successes day after day. The people participating can regard their work jointly with pride and pleasure on the day of completion of a part structure and the highly exciting day of the breakthrough or commissioning.

One should add, for the sake of good order, that the requirement for “closed spaces” applies in the field of the final examination of a construction document.

Why is it so difficult to convince the participants of the consistent application of the rules of low-conflict contract?

Unfortunately, it is extremely difficult in construction, and in underground engineering, in particular, to demonstrate the true potentials of a low-conflict contract agreement. There are, however, already some projects in which the project partners have recognised during implementation that cooperation is better than confrontation. Construction and tunnel engineering are notable for the principle of “one-off” production. The influencing factors in the project environment are extremely diverse, as a consequence of differing boundary conditions. Cooperative or non-cooperative project implementation is here only one influencing factor, which cannot be evaluated in isolation. This is what makes it so difficult to comprehend that precisely the cooperative and mutual implementation in the sense of the DAUB recommendation has resulted in the success of the project. Nonetheless, it remains the authors’ conviction that cooperative project implementation is the much more efficient and, ultimately, also significantly more cost-efficient implementation of a tunnel construction project for the benefit of all parties involved.

5 An Appeal

Tunnel construction projects with their extremely large budgets and their engineering challenges are among the most exciting engineering tasks in the field of construction. Enthusiasm for tunnel engineering must not be diminished to such an extent by the type of contract design frequently encountered today that there is a lack of committed young people and tunnelling becomes merely a matter of working off a task. The tasks coming up in the future decades are enormous throughout Europe.

Our appeal is directed to all tunnel-engineering professionals: “More cooperation, less confrontation!” should be the daily watchword in all phases of projects now and in future. The DAUB recommendation and our supplementary notes to it should not be work drafted for the distant future but instead should be the chosen path immediately.

The DAUB can be approached on this subject at any time on its homepage.

Footnote

1) The German Tunnelling Committee is a body concerned in the broadest sense with the creation of tunnel structures, its primary attention being directed to road and rail underground transport infrastructure.

1) Der Deutsche Ausschuss für unterirdisches Bauen ist ein Gremium, welches sich mit der Erstellung von Tunnelbauwerken im weitesten Sinne beschäftigt, wobei das Hauptaugenmerk auf unterirdische Verkehrsinfrastruktur von Straße und Schiene gerichtet ist.